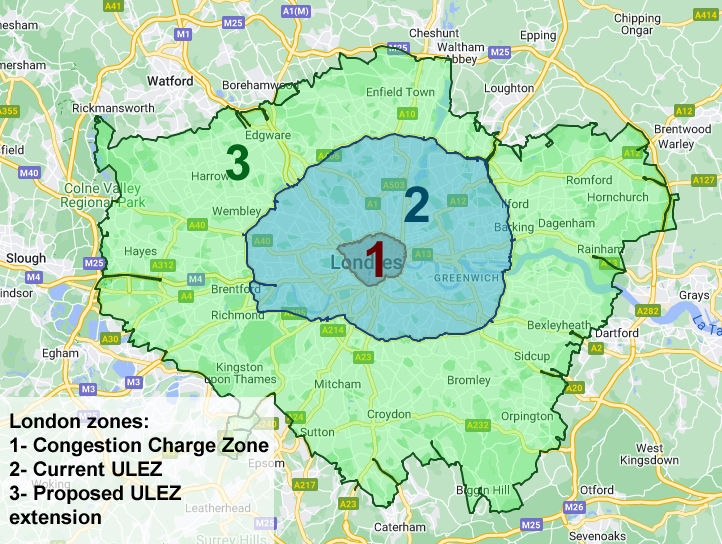

A consultation on plans to expand the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) to cover almost the whole of the capital from 29 August 2023 has been launched and will run until 29 July 2022. In this article, we will explain what is ULEZ, what is behind the different charging systems introduced in London since 2002 and how it compares with a completely different choice made in Paris to reduce vehicle impact.

Under the proposal, the current £12.50 charge should be retained but the plan proposes to scrap the £10 fee to register for Auto Pay service each year and increase the fine from £160 to £180 (£80 to £90 if you pay within 14 days).

The current consultation is also asking Londoners to help shape the future of road user charging in the capital. This could include scrapping existing charges, such as the Congestion Charge, and replacing them with a single road user charging scheme.

This latest proposal is similar to options previously envisaged to charge all out-of-town motorists entering London £3.50, or a £2-a-day “clean air charge” on all petrol and diesel cars driving in the UK capital. Although supported by the Greens and environmental groups, both ideas were strongly opposed by the Tories (Transport Secretary Grant Shapps called them “undemocratic”) and they have since been ditched.

Transport for London (TfL) estimates that the number of cars not meeting the ULEZ standards each day in outer London would initially be between 135,000 and 206,000.

- You can access the online consultation HERE.

- You can also make comments by email (cleanairyourview@tfl.gov.uk) or by post (Freepost TfL Have your say).

What is ULEZ

ULEZ, which stands for Ultra-Low Emission Zone, is an area of London where any vehicle that does not meet at least the Euro 6 standard for diesel vehicles (roughly more than 7 years old in 2022) and Euro 4 for petrol (roughly more than 15 years old in 2022) will have to pay £12.50 to enter the area.

Similar to the congestion charge (until 2021 ULEZ was actually limited to that zone) it uses a camera-based mechanism for enforcement. It costs £12.50 a day if your vehicle does not meet the tough standard and failure to pay the daily charge will result in a £160 fine, reduced to £80 if paid within 14 days.

Pollution in London has reached alarming levels, making London one of the most polluted city in Europe and therefore as become a major concern for the Mayor.

In 2014, the government published data showing that Greater London was exceeding the EU’s nitrogen dioxide (NO2) pollution limit since 2010, and was expecting to do so until at least 2030, leading the European commission and environmental lawyers to launch separate legal actions against the government.

In 2010, the Mayor of London Boris Johnson had a plan to “glue” emissions to the soil using specific suppressant techniques on the city’s dirtiest roads. However, it was a total failure. In 2014, he announced a plan to reduce pollution (albeit excluding HGV and coaches from the charge) with an ultra-low emission zone to be set in 2020.

Following record air pollution levels in January 2017, a toxicity charge, known as T-charge, was introduced on 23 October 2017 by new Mayor of London Sadiq Khan, operating in the same area and for the same hours as the Congestion Charge (CC – 7:00 am to 6:00 pm on weekdays). Older and more polluting cars and vans that do not meet Euro 4 standards (typically diesel and petrol vehicles registered before 2006) had to pay an extra £10 charge on top of the congestion charge to drive in central London, within the CC zone.

The T-charge was replaced by ULEZ in April 2019 and, this time, was made 24/7, every day of the year (except Christmas Day), with charges of £12.50 a day for cars, vans and motorcycles, and £100 a day for lorries, buses and coaches.

ULEZ was extended to the North and South Circular in October 2021 and Sadiq Kahn announced that it should be extended to the whole of Greater London from August 2023.

The unavowable goal of the Congestion Charge: generate more money for TfL

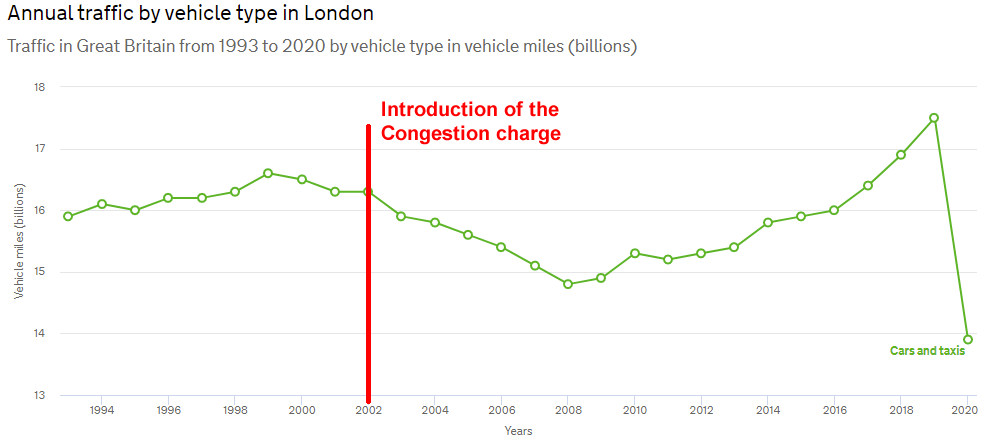

The primary aim of the Congestion Charge (CC) was to cut traffic levels and congestion in London. Or at least this was the argument used by Ken Livingston, then Mayor of London in 2002.

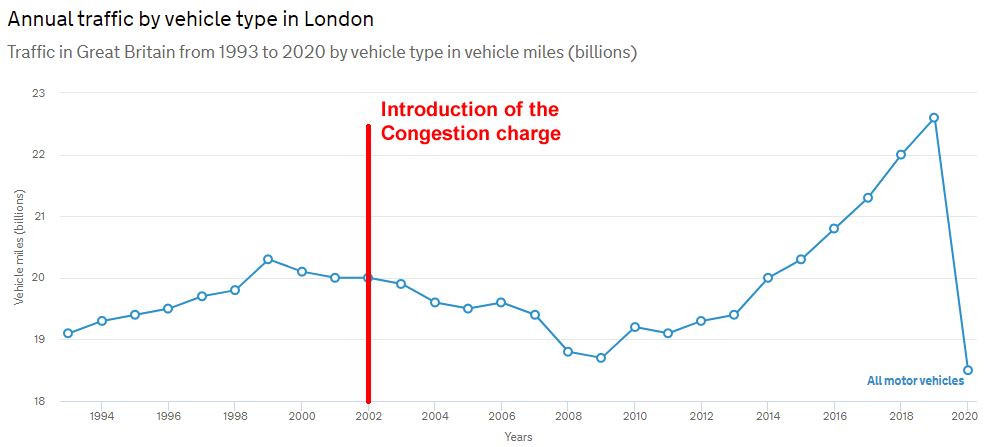

While it seemed to work initially as TfL recorded a 27% drop in traffic during the first year (i.e. nearly 80,000 less vehicles), the effectiveness of the system has fallen through the years. In a report to the London Transport Committee in January 2017, Caroline Pigeon (Libdems Assembly Member) wrote:

“Congestion has begun to increase sharply again, and not just in

central London but across the capital. Traffic has slowed down and road users are spending longer stuck in delays. Buses have become so unreliable that usage has begun to fall, after many years of growth. What is clear is that the current Congestion Charge is no longer fit for purpose”.

At the time of this report, the annual traffic by car in London was back to the 2002 level with 16 million miles recorded.

More recently, considering the pre-pandemic figures in 2020, the road usage within London increased to 17.5 million miles in 2019, despite the CC fee having more than doubled from £5 in 2002 to £11.50 (the charge was increased to £8 a day from July 2005, to £10 from January 2011, to £11.50 from June 2014, and £15 from June 2020 following a central government demand as a condition to bail out TfL).

However, the 2017 report was suggesting still more road pricing, as if the only way to discourage people to use their car was to tax them (but with the condition to allow wealthier users to ignore the objective to reduce traffic).

While it seemed to work for the first 5 years, the failure of the announced goal of the congestion charge is even more striking when looking at the trend for all vehicles, especially from 2009 onwards.

In reality, it appears that the real purpose for the Congestion Charge was to compensate the lack of support from central government for London public transport and to find alternative funding.

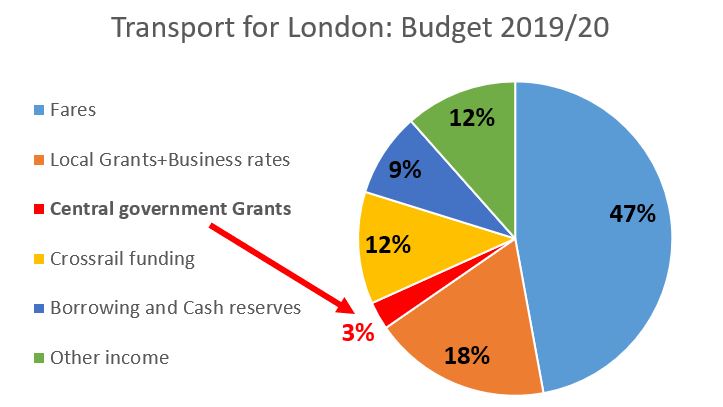

As we saw in a recent article, a report to the House of Lords published in December 2021 provides more details about TfL funding. In 2019/20, the latest year for which figures are available, TfL income and funding comes from four main sources. The latest data shows:

- fares income, which is TfL’s largest source of income (£4.9 billion);

- other income, including from commercial activity and income from the Congestion Charge (£1.2 billion);

- grants, including business rates (£3.4 billion but only £300m from Central Government); and

- borrowing and cash reserves (£0.9 billion).

In more detail, it gives the following shares:

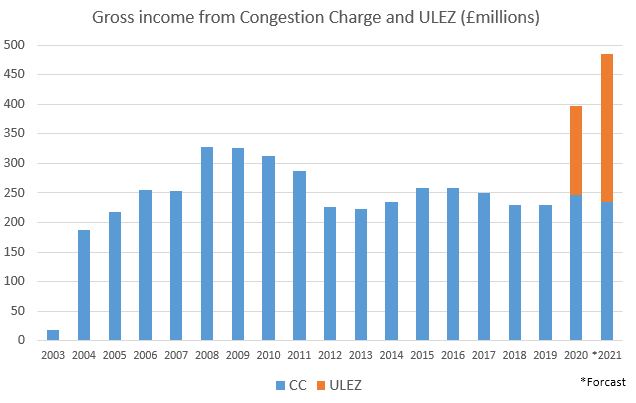

If we compare with Paris (Greater Paris has a similar budget of about £10 billions), the funding is completely different: 27% only comes from ticket sales paid by customers, while 52% is funded by employers (either through payroll tax – 41% – as in New York, or reimbursement of their employees transport cost) and 21% coming from grants from the Region, the city of Paris and other local authorities.In the 2019-2020 budget, the Congestion Charge gross income was £247m (an increase of 8% in comparison to 2018-19). The ULEZ charge for the same period was £149m. In total, even if we remove the cost paid to run and maintain the system (fees paid to Capita to set up and maintain the system cost about 30%), the amount is close to the annual grant provided by the UK government.

Transport for London in the centre of a game play

The relationship between the Conservatives government and the Labour Mayor of London is comparable to a game play: they request increase of congestion charge and cut in transport service for any additional money that they provide (they forced City Hall to bring the congestion charge to £15 a day in 2020), which confirms that they expect the congestion Charge to be a source of income for TfL while the rise of transport fees could make the Mayor impopular. Sadiq Kahn said:

“The challenge is, pursuant to the most recent deal done with the Government, they’re requiring TfL to find an additional £300 million of savings in the year 2021/22 and £730 million of savings by 2022/23, so any additional money we put into TfL would be directed towards the savings requirement from the Government.”

However, the Congestion Charge income has decreased from the record levels of 2008-2009. The new ULEZ charge represents an additional 40% income in 2020. In 2021 London expects to rake an extra £200 with the extension to the North and south Circular (still less than expected).

While ULEZ revenue is said to decrease as cars become more and more compliant to the tough regulations, the trend is only showing the exact opposite: cash generated with the ULEZ charge is increasing because … ULEZ is expanding.

With the plan extension of ULEZ to the whole Greater London by 29 August 2023, the mayor’s office estimates that an additional 135,000 vehicles a day would be affected, which means about £600m a year in additional income (if this is still £12.50/day).

In the future, local authorities are already thinking of other ways to balance the book through user charging, as explained in the 2017 London Assembly report, such as a reformed road pricing regime, integrated with other forms of paying for roads, including Vehicle Excise Duty (an annual charge for private vehicle ownership, based how polluting the vehicle is) and emissions charges.

Paris: A completely different model to achieve the same “official” goal

It is interesting to cross the channel and see how they tackle the exact same goals in another country. And we could not choose a more different approach than the one implemented in the French capital.

Reducing cars traffic by improving bus and cycles lanes and increasing pedestrian only areas

First Socialist mayor of Paris in recent times, Bertrand Delanoë was elected in 2001 on a programme including better pedestrian experience and public transport improvements. He embarked into a series of road works, reserving lanes on major routes for buses, taxis and cycles only (thus restricting cars to one or two lanes), and declared his ambition to remove motor traffic on both banks of the river Seine (which was only achieved eventually in 2012 for the left bank and 2016 for the right bank, after his departure as Mayor).

In 2007, Paris was the first city in the world to implement a large-scale public bicycle sharing service (it was followed by London in 2010, but with a much smaller scheme). It was part of Delanoë’s idea of making the city more ecologically friendly and reducing traffic by making taking a car into town unattractive.

Britannica encyclopaedia says:

“Delanoë had his biggest and most controversial impact on the city’s traffic system. He embarked on a series of measures to discriminate against cars in favour of other forms of transport. These included closing the Seine riverbank roadway for part of the summer (and transforming the riverside into a series of beaches, known as the Paris Plages), adding new bus lanes on main boulevards, and establishing studies on the reintroduction of trams and more use of the Seine to carry cargo. He later introduced a citywide pay-as-you-ride bicycle service.”

All of that without any specific charging system, although it also attracted the anger of many car drivers.

However, the Parisians loved it and he was easily re-elected in 2008. Delanoë left office at the end of his second term in 2014, still highly popular. He was succeeded by Anne Hidalgo, who was previously deputy-mayor for 2001-2014. She has since carried on with similar reforms to reduce cars in the French capital.

No compromise on pollution: full ban on old vehicles

In 2015, Paris set up a Low Emission Zone (LEZ) called ZFE (Zone à Faible Emission) and many large cities followed in France (Marseille, Grenoble, Lyon, Lille, Strasbourg, Toulouse …).

In order to be able to drive within a ZFE, you need a mandatory sticker called Crit’Air (Certificats qualité de l’air = air quality certificates) for French and foreign vehicles. The sticker costs €4.51 (including postage) per vehicle. In practice, rules are similar to the ones in London, where vehicles with Euro-4 standard of emission or newer are allowed to enter the city.

From June 2021, all vehicles with Crit’Air 4 and above are totally forbidden within the zone (older than Euro-4 standard – for example, you cannot drive with a diesel car older than 2006; and in 2024 you won’t be able to drive with a pre-2011 new diesel or petrol vehicle – Crit’air 3 and above, or Euro-6 will be the minimum requirement).

There is no by-pass (except for vintage cars) and failing to comply with the requirement will occur a fine of up to €450 (in practice usually €68).

The environmental restriction in Paris leads to a full ban of vehicles considered to pollute the most; the result is immediate (within the category of ban) and it cost little money for its implementation (there is no network of cameras to be installed to filter vehicles entering the zone).

As in London, Paris mayors had very clear and unique goals:

- from 2001, restricting access to cars in Paris by making their use more difficult, while encouraging alternative transports (by the way, e-scooter and monocycles have been used successfully in the French capital even before the arrival of several hiring companies in 2018… while 5 years later, London is still “experimenting” the schemes and have banned them from the public transport network);

- and from 2015, reducing pollution with a ban on older cars.

Greenpeace published in 2018 (before both London-ULEZ and Paris-ZFE implementation) a study on sustainability transport and air-quality in 13 European capitals named “Living. Moving. Breathing.” and may provide some hint on the efficiency of the different approach: Paris seats in the middle of the ranking, while London is at the bottom, only better than Moscow and Rome.

Criticisms of the efficiency of charging rather than banning

In comparison, it seems that London has followed Paris each time but with a specific scheme primarily design to make money. A sort of permit to drive if you can pay for the congestion charge, and a permit to pollute for the ULEZ. You are free to drive with your vehicle and pollute as much as you want, as long as you pay the necessary tax.

The choice of a paying system where you can drive and pollute if you prefer to pay rather than a more coercitive option has raised criticism on the efficiency of the model.

The 2017 report cited above said:

“The Congestion Charge is not necessarily the only reason for this shift, with car traffic already falling prior to its introduction, and improvements in public transport giving Londoners better alternatives to car travel. “

Until 2014, it could be argued that it has effectively reduced congestion. However, more recent data dismiss completely the argument, showing a vehicle usage 10 % higher than when the Congestion Charge was first introduced and the trend rising.

There is little doubt that ULEZ will have a positive effect in the air quality in the city, as an incentive for many to upgrade their vehicle or use alternative transport. However critics are questioning the level of enthusiasm of supporters to show immediately huge benefits.

Sky News reported last year that researchers from Imperial College London have found that ULEZ policy in London resulted in only small improvements in air quality soon after it was implemented. They also found the biggest pollution changes all took place before the ULEZ came into effect in 2019, according to the media. Even a press release from City Hall said:

“Traffic flows may also have been influenced by other changes, such as the removal of the exemption for private hire vehicles from the congestion charge.”

A system primarily designed to make money for London

The Mayor of London was not showing total honesty when declaring (in 2018):

“The introduction of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) in 2019 and its expansion to inner London in 2021 is not about making money, but about improving the health and wellbeing of thousands of Londoners.”

According to the web magazine Londonnewsonline citing a recent survey, two-thirds of London drivers think ULEZ is a money-making scheme by cash-strapped TfL. It says:

“Vehicle finance company Carvine conducted a survey to find out what Londoner’s really think about the scheme. Of the 3,800 survey respondents, 62 per cent believe the scheme is financially motivated.”

That the Tory party thought that the future would be with cars when in powers in the 80s (the “great car economy”), that they decided the disastrous privatization of the rail system in the 90s, that the Labour leadership with Blair and Brown did not really inverse the trend despite the favourable economic environment and that, since 2010, the Conservatives have hold government power and cut funding, has certainly been an important factor in the small number of options available to improve public transport in London.

And the fact that the Tory government is nowadays playing hard ball by restraining public transport funding to the city, in order to undermine the Labour mayor public record, does not help either.

One could consider that for the last 20 years, London has not had much choice in its transport policy. Six months ago, the Daily Telegraph was saying that London public transport is at risk of returning to the state of the 1970s and 80s with TfL set for “managed decline”!

In a sharp criticism of ULEZ, Mike Rutherford, Chief Columnist at Auto Express, said:

“Yet as long as the drivers of [polluting] vehicles each stump up £12.50 a day, they can continue driving their ‘health-damaging’ motors. If they’re as bad as Khan claims, why doesn’t he just ban them? Because he wants those £12.50-per-day fees.”

Unfortunately, that could be the only option to keep London public transport afloat currently.

But most would agree that the ambition of the UK capital deserves more transparency when it comes to its measures against cars and to improve alternative transport and life conditions.

Wandsworth Council reaction to the 2021 ULEZ extension to the South Circular

Although the Mayor of London confirmed the ULEZ extension to the South Circular in 2018, it’s only at the end of 2021 that Wandsworth Council seemed to wake up and realize that the new boundary would include the waste and recycling centre in Smugglers Way.

Wandsworth Council’s transport spokesman, Cllr John Locker, said:

“It cannot be right that residents who are doing the right thing and making the effort to recycle or deposit their waste in the right place should be penalised for doing so.

If they are simply entering the zone to do their civic duty and then leaving straight away and not venturing further into the charging area, then they shouldn’t have to pay for it.”

However, their attempt to exempt vehicles utilising the waste facility has failed.

The fear that the £12.50 charge for vehicles that do not comply with the ULEZ rules would lead to more fly-tipping might exacerbate with the planned extension.

Wandsworth’s environment spokesperson said last year that instead of paying the £12.50 charge to get to the Recycle centre, residents could “book a simple and convenient pick-up service from the council instead“. However, it ignores the cost of the service, which is a minimum of £20.60 and £9.20 for each additional item after the fourth one. In addition, for residential landlords it costs from £88 to £175.40.

That might be an opportunity to rethink the current options to dispose of bulk items.

During the local election campaign last May, there were discussions about regular “Mega skip” days and even a proposal for free bulk item collection for a limited number of times a year to discourage fly-tipping, on the model of the free service to dispose hazardous operated by the City of London and available to Wandsworth residents.